Text by

Photos by

Balloon Hats by

"Where you going?" the woman asked, standing in the middle of the street. "You go to Busua?"

"We don't know where we're going. What's Busua?"

"Very beautiful there. My home. I take you there. Follow me."

"Is it on the ocean?"

"Yes. Beach and fishing. Come, follow me."

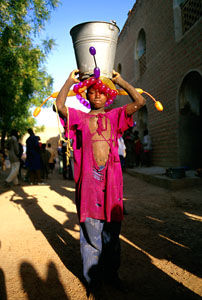

No arguments there. The four of us climbed into the back seat of a small Toyota (there were three others in front) and bounced down the dirt road to Busua, a small fishing village on Ghana's Cape Coast. Toward the end of the ride, Addi wasn't talking anymore. Charlie wondered whether he was still conscious, since everyone had been piled on top of him. When we got out in Busua, Addi explained that he hadn't quite passed out, but that the weight of everyone's bodies along with the impact of driving through some large sinkholes in the road had forced all the air from his lungs. Busua then, not a moment too soon. A balloon hat twister with collapsed lungs is no one's idea of a party — that is if he actually was what he claimed to be. Although he had told me three-quarters of his backpack was full of balloons, I hadn't yet seen one.

The woman led us to her friend Elizabeth's guesthouse, a cement block structure and some steel-roofed huts around a central court. The sanctuary of the Musama Disco Christo Church, of which Elizabeth was an elder, formed the remaining side of the compound. The local children who attempted to carry, and ended up dragging Charlie and Addi's massive bags seemed confused that neither one of them was particularly interested in seeing Fort Metal Cross, one of the sixteen old slave-trading forts that dot the Cape Coast of Ghana, and the primary reason tourists come to Busua at all. Addi would merely say, "maybe later," as he and Charlie continued to poke around, muttering lighting and backdrop logistics to each other.

After

dark in our small hut, Addi pulled out some balloons and began twisting

practice shapes for what he knew would be his African debut the

next day.

"You

weren't kidding," I remarked as I drew down the holey mosquito net

and began the evening's anti-malarial ritual. After a few satisfying

kills I sat down and asked him how he'd picked up his craft.

As he lay on his back, knees bent, with a yellow balloon twisting into knots over his face, the kerosene lamp on the floor cast giant balloon shadows on the ceiling, turning the hut into more of a mad scientist's laboratory. He described the three months in his bedroom at home, crying over a lost love, mindlessly twisting balloons to keep his hands occupied — above his waist. And here he was, probably in the same position he'd held for those three months learning to twist balloons into sculpture because his grief would allow nothing else.

Measuring more balloons, he explained he'd been thinking about a new hat design during the excruciating, six-hour, minibus ride in order to take his mind off the pain the makeshift wooden seat had given him. More pain, more balloon hats. This one was turning into a woven web of four colors as he lay on the cot, squeaking and popping the twists, complaining about the intense humidity's effects on balloon performance. Laughing children could now be heard whispering outside the window.

A

hard rain came the next day, and not surprisingly "Balloonhat" decided

to postpone any performance. It happened to be Palm Sunday and there

were far more than the usual worshippers in attendance at the Musama

Disco Christo Church just ten feet away from the damp hut. Throughout

the Christian/Animist hybrid rituals of a three-hour service, village

children wearing balloon hats would wander in and out of the shelter,

their hands feeling up and down the contours of elaborate new headdresses

Addi had made for them. Obviously, he hadn't been able to help himself

entirely.

I'd first encountered these two serious young men in the currency exchange line at the airport in Accra, the capital of Ghana, where Addi just happened to be standing behind me. I had come to Africa on frequent flyer miles as part of an egoistic attempt to call myself well-traveled by meeting West Africans and listening to their music firsthand. Wondering whether anyone else's trip could possibly have been as pathetically half-baked, I asked Addi what had brought him to the region, expecting to hear that he'd come for a vaccination project with some Western aid group. Northern Ghana was in the midst of an unusually harsh meningitis epidemic and the only other non-Africans on the flight had indeed been Doctors without Borders. Instead, to my surprise, he hesitated with a sidelong glance as if to prepare himself for the usual response, and explained that he had come to Africa to make balloon hats. When I asked him if USAID or the Peace Corps had sanctioned such an absurd idea, he explained that he and his partner, a photographer documenting the experience, were financing the project out of their own pockets. By this time Charlie had arrived with their bags as my night's worth of money was being counted out under the change window. After a few pleasantries, I wished both of them luck with an eye-rolling smirk and disappeared into a chaotic airport crowd expecting never to see them again.

Two days later there they were, though, boarding the same small bus (known as a tro-tro in Ghana) with the same vague idea of ocean in mind. I was crushed in next to an officious Ashanti gentleman in a suit and spectacles. He had spoken at length about his job for a government development agency and his mandate to find a solution to the problem of street children in the cities of southern Ghana. Two hours into the trip he stopped talking and started vomiting into a Notre Dame T-shirt on top of the briefcase on his lap. My leg was getting the overflow. I glanced back at Charlie and Addi bouncing miserably in the back seat. The look on Charlie's face told me he was feeling no less pain than I. A town like Busua couldn't have been a better place to end such a ride.

Though, as is the case almost anywhere Westerners go to try and escape everyone else of their kind, we soon found we were not the only visitors around. One walk to the village well revealed two Scotsmen sitting perched on the stoop outside some random hut, tripping heavily on spacecakes they'd bought from the local Rasta drummaker. It looked as if the Scotsmen had set up their new Ghanaian peg drums outside with the intention of practicing the "Kpanlogo" or first rhythm of coastal Ghanaian drumming, but instead had forgotten who they were, much less why they had come to the village in the first place. The one thing they probably hadn't forgotten, indeed the only thing that seems impossible to forget in any altered state of mind, is that they were in Africa. They had just returned from the Dogon region of Mali with tales of robbery and harassment, and needed decompression on the coast before returning home. "We're glad we went and got through it, but we would never go back."

Though the Scots' stories centered on their difficulties in finding an honest guide in all of Mali, they also mentioned their planned visit to Timbuktu, that proverbial most-inaccessible place on earth, had been thwarted by all manner of obstacle — from thieves in Bandiagara, to warnings of Tuareg unrest in the region, to lack of any certain overland route — and they had decided that for them it probably would remain the most inaccessible place on earth.

Listening with open mouths to the Scots' hallucinatory memories, Balloonhat seemed to revel in the sheer happenstance of it all, and right then under the full moon a tangible goal for their African Balloon Hat Experience began to rise out of the very thick air.

Timbuktu. Balloonhat had heard of it before, but where exactly was it? To discover that it was here in West Africa and perhaps only a thousand kilometers north gave rise to the quixotic challenge Balloonhat seems to need from every journey. An overland dash from a sixteenth-century slave-trading fort to the edge of the Sahara where exotic hats from the West could be traded for photos of people rarely seen outside the region; that would be the easy part. The hard part, all agreed, would be to make it back to the coast by the next full moon in order to board the nonrefundable flight out to another part of the world.

The Scotsmen returned to their hallucinations with serious doubts about the success of such an endeavor. Nevertheless, they smiled at the idea and wished Balloonhat luck with eye-twitching smirks.

The Journey

An

hour north of Accra, at the southern tip of Lake Volta, the largest

artificial lake in the world, a freight barge christened Buipe Queen

makes its weekly port of call at Akosambo, bringing yams, goats,

and other cargo from the Upper East Region of Ghana to city markets

nearer the coast.

The Buipe Queen cruises the lake at around ten knots with a deck full of empty crates, stopping occasionally to take on cargo and passengers. During most of the daylight hours no one can move. As is the case every day in this region, during the high-sun hours people don't talk. Lying around in empty crates on deck, half-asleep, they rest heads on elbows, staring sideways into space, knowing they're trapped in a hundred-twenty-degree floating oven. Even the galley maid who is supposed to be on shift cannot help but pass out over her counter. If anybody wants to eat, they have to be satisfied only thinking about it. But then as simultaneously as any African town seems to awaken itself, people stir a bit all at once — maybe think about moving for some bit of sustenance — and the late afternoon comes alive with conversation and a new shift of work for the crew.

It was here among swarms of lake flies too numerous to swat that I asked Charlie how he happened to find himself sleeping on tables and cement floors halfway across the world for the dubious privilege of shooting photos of people in balloon hats. His answer was simple. To see the look on a child's face, to discover people's universal need to laugh, to find the connection to humankind strengthened by the smallest gift of color, had become more than addictive. It had become his only purpose.

He said he'd first noticed people's reactions to Addi's hats on a Halloween night in New York the previous year. After a group of four of them had failed to come up with any costumes for a friend's party, Addi, who was then only a vague acquaintance, offered to make hats for all of them and fulfill the costume requirement without too much work. The moment they stepped onto the street, though, Charlie was amazed at the awe-struck responses to the hats. He had walked these streets his whole life without so much as drawing a glance, and here were total strangers smiling, laughing, eager to converse. The next morning, hungover at the breakfast table, he wondered aloud to Addi whether taking the hats to people all over the world might be a cool thing to do. He hadn't quite realized how seriously Addi had taken him until a couple weeks later when Addi called and told him he'd cleared his schedule and was ready to begin the project.

Now here he was, in the middle of the hot season in West Africa, lying on top of a table with flies stuck to his face, wondering when the cool part of the idea would occur to him again.

Thirty-two hours after the Buipe Queen's departure, Balloonhat and I debarked from the freighter on Lake Volta's northern shore, where there still remained another twenty-four hours of almost continuous travel by dump truck, minibus, and small, beaten sedan before reaching Bolgatonga, the capital of Ghana's Upper East Region. In Bolga, we could rest for a day or two and figure out the shortest way across the border to Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, and from there into Mali, and with luck, Timbuktu.

Mad Dogs and Balloonhatmen

Solomon, our local man in Bolga, actually a seventeen-year-old on break from the Navrango Secondary School who had marked us getting off the dusty bus, magnanimously offered to act as guide to the nearby village of his birth.

In a rented yellow Toyota, Solomon brought us five clicks on a dirt road southwest of town where we parked underneath a lone Baobab tree, looking beyond a few goats to a settlement of painted adobe huts well away from the road. The inhabitants could not have known what awaited them. Nor could Solomon for that matter.

Laboring with bags of cameras and balloons over dusty, cracked earth in the heat of another hundred-ten-degree day, Charlie noticed Addi had forgotten to bring his hat. He walked up next to him and asked how he was feeling.

"Nauseous. Dizzy. I might pass out." Addi had been vomiting and feverish since the previous evening's arrival in Bolga. And though none of us could utter the word, some strain of malaria seemed a likely scenario in our paranoid American minds. Of course it turned out to be his anti-malarial medicine, but that would take another few weeks to figure out.

"Can you make any hats?" To that Addi gave a look of hopelessness, knowing he could do nothing else now that he had come this far.

He

lasted for a respectable five or six hats before turning to a bizarre

shade of off-white, and back in the car he explained that he had

basically gone on autopilot---blow and twist, blow and twist —

and at the moment didn't know whether he would even be able to get

out of the car at the next stop. But during the short drive to the

next settlement, as Charlie mentioned the approach of near-perfect,

late afternoon light — the golden hour — Addi knew he

would have to drag himself out of the car again and somehow manage

to keep going until the sun was gone.

At the next settlement Charlie entered a frenzy of shooting unlike any before it. The sun was low, truly gold, enhanced by the reddish dust of the earth in the region. The sky was perfect too — a brilliant blue with giant cumulus clouds adding depth to the scene — a landscape completely different from that of the jungles of coastal Ghana. The Balloonhat had reached the edge of the Sahel, the great buffer zone between the ever-expanding Sahara Desert to the north and the rainforests of equatorial Africa to the south. And Charlie was, without question, trancing to the light's effects. He continued shooting long after Addi had stumbled back to the car, waiting in the back seat to die.

On the way back to Bolga as Addi hung his head out the window, our driver swerved to avoid a stray dog in the middle of the road. Solomon seemed strangely disappointed in this. A moment later he casually mentioned that both the Dagete and Grune people of Northern Ghana like to eat dog meat. According to Solomon, they not only like the taste of it, but they also believe a man will die at home rather than during his travels if he eats the sacred flesh of a dog raised for this specific purpose. As Addi seemed to be getting sicker by the hour, it was unanimously decided that a dose of dog from the new market in Bolgatonga might be the only way to get him back to the States intact.

New Marketing

The new market is a place where men buy and sell goat kids and black and white checkered guinea fowl, or sit under corrugated steel-roofed shelters drinking pito, a sour, fermented millet wine, out of large calabash bowls as they recline and listen to the spare sounds of lute and shaker.

Over in the dog meat shelter six men sat in a row at a wooden table, whiling away the afternoon, eating chunks of dog sprinkled with hot red pepper freshly crushed in a nearby mortar and pestle. Solomon suggested buying a thousand cedi's, or about sixty cent's worth of meat and choice organ slices to make enough for everyone back at the hotel. There can be no doubt as to the animal it has come from either. The butcher leaves the leg and rear paw on the boiled meat, and unmistakable jawbones lay strewn on the ground beneath the table seeming to say "You've tried the rest, now try the best."

A thousand cedi's worth turned out to be over a pound of flesh. It seemed much of it would be wasted.

Back at the hotel the meat was spread out on a night table, and inspection began. As I was reading a particularly interesting piece of liver, Solomon's fingers grabbed it and popped it in his mouth. It became apparent then that if Addi didn't rise up from his death bed soon for a piece to chew on, Solomon would eat the entire pound, compulsively, like snack food, leaving nothing for the cure. Eventually, with some prodding, Addi forced a couple pieces down and fell back hard on the bed.

Five days into the journey here, we could only worry that if the illness didn't suddenly improve, his life would possibly be in danger, making the goal of Timbuktu unattainable. Fortunate then that Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, happened to be the closest city with any substantial medical facility and also happened to be on the way to Timbuktu. Addi basically had no other choice but to press on and make the dusty four-hour ride by broken dirt road through a desolate border zone, putting us that much closer to the goal, whether the dog meat would ultimately succeed or fail at its job.

_____________________

features | archive | editor's note | letters | contributors | contact us